One of the challenges of writing distance-learning material is that you are, fundamentally, imagining the students who will use it, rather than having them in front of you as you deliver it.

We know the demographic characteristics of students in my Faculty (predominantly: female; already working in the care sector; in their 30s and 40s; more likely to be disabled or BME than the general population; low rates of prior educational qualifications; on lower incomes, although all this may change under the new funding arrangements in England). There are also lots of quality-assurance mechanisms in place to try to make sure that what authors write does connect to actual students, but it doesn’t happen in real time. You start off with just you, the author, sat in a room imagining someone reading your text and doing the activities you suggest.

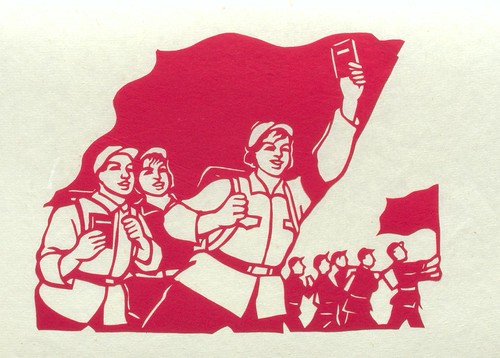

(cc) Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library

How you have imagined the students matters particularly when you are asking them to make connections between their own experiences and what they are learning, a staple of the approach to teaching in my Faculty. If you make assumptions about their experiences and knowledge that aren’t the case, at best they can’t do the activity, at fairly-bad they feel temporarily excluded or invisible and at worst, if it happens too much, they drop out feeling the course is not meant for them.

What follows is my personal list of things that the author may assume about students that are not always the case. It is, of course, incomplete. Please do add suggestions.

Students may not…

- be like our typical students – so they may not be female, in their 30s and 40s and so on. Because we have had such a clear demographic, which is so different from the average undergraduate, there’s a danger of overgeneralising it. Some of our students are young, white, male, able-bodied and with good ‘A’ levels. Astonishing! (I love the fact that this possibility genuinely does seem unlikely and surprising. Hooray for the OU)

- share cultural references that authors think ‘everyone knows’ whether that is Eastenders, The Archers or X-Factor.

- have English as their first language – idiom and ‘sayings’ can be particularly difficult.

- know things about the care system if we haven’t taught them, even things the author thinks ‘everybody knows’.

- have low entry qualifications – some have excellent study skills – don’t teach them to suck eggs.

- have good computer access. They have to have computer access to study nearly all our modules, but they may not have a home computer – they may use one at work on in a library. If they do have a home computer, their connection may be too slow to watch video clips. A particular issue with our demographic is that they may have to fight their children to get access to the computer. All of these make a difference to how centrally you design the online elements of a module – you can do loads of really interesting and useful things online, but it’s no good if students can’t really access it.

- have had a traditional/normative life course; they may not be heterosexual, they may not have a family, they may not have known their biological parents, they may not have been raised by their parents.

- be willing to reflect on their life course (including because it may be too painful).

- be working in care. They may be care users[1], which often gives you a very different perspective on lots of issues. They may be both a care user and a care provider. They may also be informal carers. A few, a very few but we still have to allow for them, may have no personal connection to the world of care at all. They may be studying for purely academic reasons. Astounding again!